THE CALL OF THE WILD, WHITE FANG

Jack London’s two most beloved tales of survival in Alaska were inspired by his experiences in the Yukon during the Klondike Gold Rush. Both novels grippingly dramatize the harshness of the natural world and what lies beneath the thin veneer of human civilization.

The canine hero of The Call of the Wild is Buck, a pampered pet in California who is stolen and forced to be a sled dog in the Alaskan wilderness. There he suffers from the brutal extremes of nature and equally brutal treatment by a series of masters, until he learns to heed his long-buried instincts and turn his back on civilization. White Fang charts the reverse journey, as a fierce wolf-dog hybrid born in the wild is eventually tamed. White Fang is adopted as a cub by a band of Indians, but when their dogs reject him he grows up violent, defensive, and dangerous. Traded to a man who stages fights, he is forced to face dogs, wolves, and lynxes in gruesome battles to the death, until he is rescued by a gold miner who sets out to earn his trust.

600

450

THE BURNING GOD (3) (PB)

After saving her nation of Nikan from foreign invaders and battling the evil Empress Su Daji in a brutal civil war, Fang Runin was betrayed by allies and left for dead.

Despite her losses, Rin hasn’t given up on those for whom she has sacrificed so much—the people of the southern provinces and especially Tikany, the village that is her home. Returning to her roots, Rin meets difficult challenges—and unexpected opportunities. While her new allies in the Southern Coalition leadership are sly and untrustworthy, Rin quickly realizes that the real power in Nikan lies with the millions of common people who thirst for vengeance and revere her as a goddess of salvation.

Backed by the masses and her Southern Army, Rin will use every weapon to defeat the Dragon Republic, the colonizing Hesperians, and all who threaten the shamanic arts and their practitioners. As her power and influence grows, though, will she be strong enough to resist the Phoenix’s intoxicating voice urging her to burn the world and everything in it?

1,450

1,088

THE BURNING GOD (3) (HC)

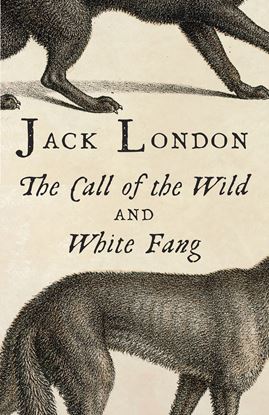

Frodo and the Companions of the Ring have been beset by danger during their quest to prevent the Ruling Ring from falling into the hands of the Dark Lord by destroying it in the Cracks of Doom.

Now they continue their journey alone down the great River Anduin—alone, that is, save for the mysterious creeping figure that follows wherever they go.

This elegant hardcover—now available for the first time in the United States—is one of five Collector’s Editions of Tolkien’s most beloved works, and an essential piece of any Tolkien reader’s library.

1,995

1,496

THE BRIGHT SWORD

A gifted young knight named Collum arrives at Camelot to compete for a place at the Round Table, only to find that he’s too late. King Arthur died two weeks ago at the Battle of Camlann, and only a handful of the knights of the Round Table are left.

The survivors aren’t the heroes of legend like Lancelot or Gawain. They’re the oddballs of the Round Table, like Sir Palomides, the Saracen Knight, and Sir Dagonet, Arthur’s fool, who was knighted as a joke. They’re joined by Nimue, who was Merlin’s apprentice until she turned on him and buried him under a hill.

But it's up to them to rebuild Camelot in a world that has lost its balance, even as God abandons Britain and the fairies and old gods return, led by Morgan le Fay. They must reclaim Excalibur and make this ruined world whole again—but first they'll have to solve the mystery of why the lonely, brilliant King Arthur fell.

995

746

THE BOOK OF LOVE

The Book of Love showcases Kelly Link at the height of her powers, channeling potent magic and attuned to all varieties of love—from friendship to romance to abiding family ties—with her trademark compassion, wit, and literary derring-do. Readers will find joy (and a little terror) and an affirmation that love goes on, even when we cannot.

Late one night, Laura, Daniel, and Mo find themselves beneath the fluorescent lights of a high school classroom, almost a year after disappearing from their hometown, the small seaside community of Lovesend, Massachusetts, having long been presumed dead. Which, in fact, they are.

With them in the room is their previously unremarkable high school music teacher, who seems to know something about their disappearance—and what has brought them back again. Desperate to reclaim their lives, the three agree to the terms of the bargain their music teacher proposes. They will be given a series of magical tasks; while they undertake them, they may return to their families and friends, but they can tell no one where they’ve been. In the end, there will be winners and there will be losers.

995

746

THE BOOK OF ELSEWHERE

She said, We needed a tool. So I asked the gods.

There have always been whispers. Legends. The warrior who cannot be killed. Who’s seen a thousand civilizations rise and fall. He has had many names: Unute, Child of Lightning, Death himself. These days, he’s known simply as “B.”

And he wants to be able to die.

In the present day, a U.S. black-ops group has promised him they can help with that. And all he needs to do is help them in return. But when an all-too-mortal soldier comes back to life, the impossible event ultimately points toward a force even more mysterious than B himself. One at least as strong. And one with a plan all its own.

In a collaboration that combines Miéville’s singular style and creativity with Reeves’s haunting and soul-stirring narrative, these two inimitable artists have created something utterly unique, sure to delight existing fans and to create scores of new ones.

1,350

1,013

THE BLACK PHONE [MOVIE TIE-IN]

Jack Finney is thirteen, alone, and in desperate trouble. For two years now, someone has been stalking the boys of Galesberg, stealing them away, never to be seen again. And now, Finney finds himself in danger of joining them: locked in a psychopath’s basement, a place stained with the blood of half a dozen murdered children.

With him in his subterranean cell is an antique phone, long since disconnected . . . but it rings at night anyway, with calls from the killer’s previous victims. And they are dead set on making sure that what happened to them doesn’t happen to Finney.

1,100

825

THE BEST AMERICAN SCIENCE FICTION AND.

“The most important part of this magic trick is just a willingness to get weird.” The stories in The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2023 are brimming with bizarre and otherworldly premises. Women can’t lie or fall in love. Fathers feed their children ghost preserves. Souls chase one another through animal incarnations. Yet these stories are grounded deeply in our reality. Out of these stories’ weirdness emerges the cruelty of border enforcement, the horror of legislation restricting reproductive freedom, the frightening pace of AI. The result is a stunning, immersive, intensely felt experience, showing us less of what the world is, and more of what it could be.

1,250

938

THE BEAUTIFUL AND DAMNED

Fitzgerald’s second novel, a devastating portrait of the excesses of the Jazz Age, is a largely autobiographical depiction of a glamorous, reckless Manhattan couple and their spectacular spiral into tragedy. Published on the heels of This Side of Paradise, the story of the Harvard-educated aesthete Anthony Patch and his willful wife, Gloria, is propelled by Fitzgerald’s intense romantic imagination and demonstrates an increased technical and emotional maturity. The Beautiful and Damned is at once a gripping morality tale, a rueful meditation on love, marriage, and money, and an acute social document. As Hortense Calisher observes in her Introduction, “Though Fitzgerald can entrance with stories so joyfully youthful they appear to be safe—when he cuts himself, you will bleed.”

995

746

![Mostrar detalles de THE BLACK PHONE [MOVIE TIE-IN] Imagen de THE BLACK PHONE [MOVIE TIE-IN]](https://www.cuestalibros.com/content/images/thumbs/0160397_the-black-phone-movie-tie-in_415.jpeg)